CURATOR’s EYE

A view far away, a heart near

Follow TRiCERA on Instagram and check out our creative artists

5%OFF & free shipping 1st purchase

FIRSTART5

10%OFF 2nd purchase after 1st purchase!

Welcome to TRiCERA

Hi there! We are pleased to have you here 🎉

Could you please describe yourself?

Guest

Best known for her floral paintings, New York City cityscapes, and New Mexico mountain landscapes, Georgia O'Keefe was an active 20th century American artist.

In the early 20th century, O'Keefe was at the forefront of American Modernism as a female artist, a rarity at the time, and was regarded as a leading figure in the movement.

She is known for her paintings of flowers, in which colorful blossoms are enlarged to create the appearance of abstraction, as well as her landscapes of New Mexico, which she worked on in her later years.

In this issue, we will take a look at O'Keeffe's life and the major influence she had on contemporary art.

Red Canna, 1924.

Born: November 15, 1887 - March 6, 1986 (died at age 98)

Birthplace: Wisconsin, U.S.A.

Art Movement: American Modernism, Precisionism

Education: Art Institute of Chicago, Art Students League of New York, Columbia University

Associated People: Alfred Stieglitz, husband, leading American photographer and art dealer

Georgia O'Keeffe was born in 1887 in a farming family in Sun Prairie, a town not far from Lake Michigan, one of the Great Lakes of the United States.

The O'Keefe family had seven siblings, and Georgia was the second child from the top.

O'Keeffe was known for his extremely precocious artistic talent and decided to become a painter at the tender age of 10. Along with his sisters Ida and Anita, he began studying with a local watercolorist named Sarah Mann.

In 1905, at the age of eight, he enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago. There, he was consistently rated at the top of his class.

He took a leave of absence from school in 1906-7 due to typhoid fever, and in 1907 he entered the Art Students League in Manhattan, New York.

In 1908, he won the Art Students League's Still Life Award for his painting "Dead Rabbit with Copper Pot.

As a bonus for winning this prize, she traveled to New York City, where she toured the art gallery 291, which was co-owned by her future husband, Alfred Stieglitz.

Dead Rabbit and Copper Pot, 1908

After his parents' business and health misfortunes left him without funds to continue his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts, O'Keeffe quit school in 1908 and began working as a professional illustrator.

He worked until 1910, and then moved with his family to Charlottesville, Virginia, that same year, despite a bout of measles and other illnesses.

At this time, he stopped oil painting for about four years, and it is said that he later said that the smell of turpentine oil made him sick.

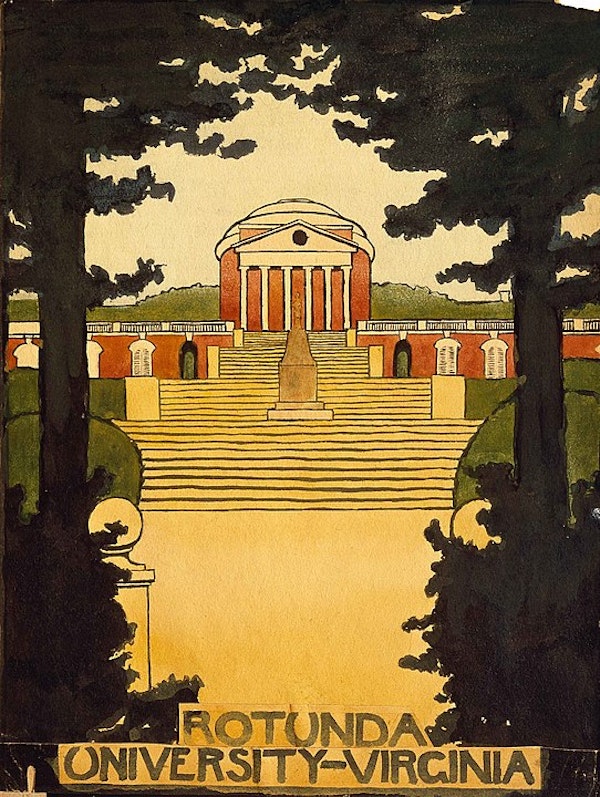

It was here that O'Keeffe attended a summer school for art courses at the University of Virginia, where he was exposed to the style of a painter named Arthur Wesley Dow, and was struck by its freshness.

His style was highly design-oriented, influenced by the Japanese art that dominated the Parisian art world at the time, and O'Keeffe began experimenting with more flat compositions, replacing the traditional realism of his earlier work.

From 1912-14, he taught art classes and worked as a teacher in Amarillo, Texas.

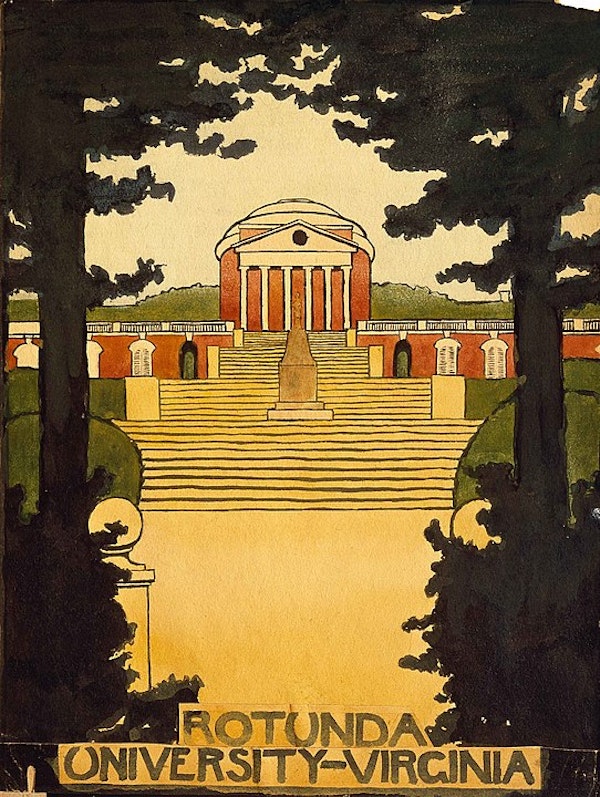

Untitled (Rotunda at the University of Virginia), 1912 - 1914

In 1915, O'Keeffe taught an art course at Columbia University.

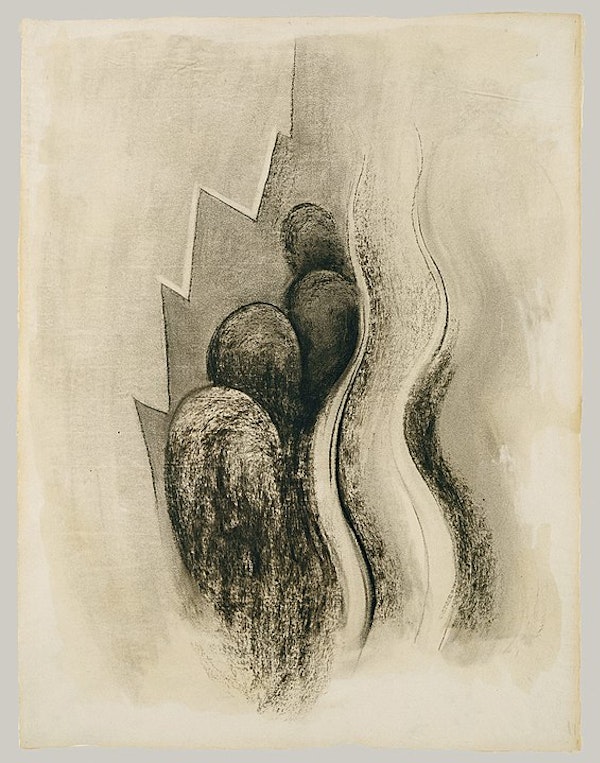

The charcoal drawings she was working on at this time gave form to her own inner feelings and began to show her creative expression.

The drawings were sent to a friend of O'Keeffe's and eventually caught the eye of Stieglitz at 291 Gallery.

He praised O'Keeffe's work as "the purest, most beautiful, and most sincere thing I have seen at 291 for some time now," and in April 1916, ten of O'Keeffe's drawings were exhibited at the 291 Gallery.

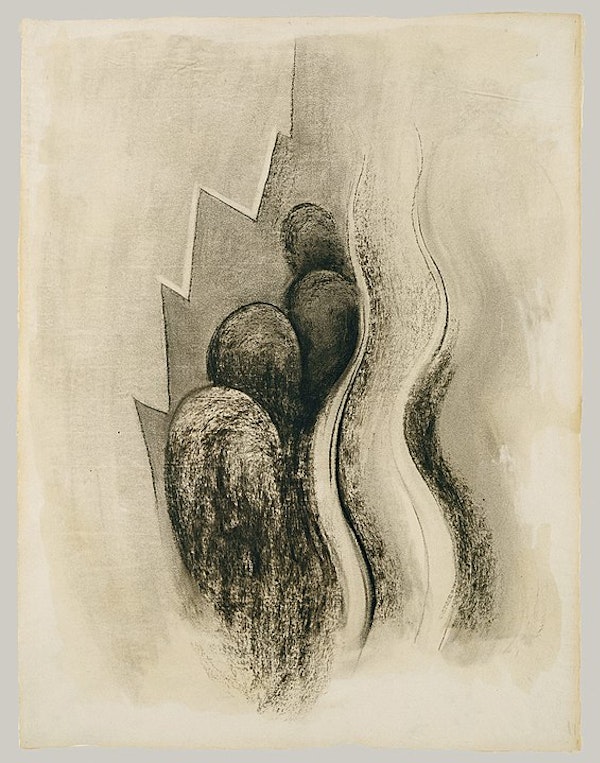

Drawing 13, 1915

After completing his work in Columbia, Keefe moved to Texas.

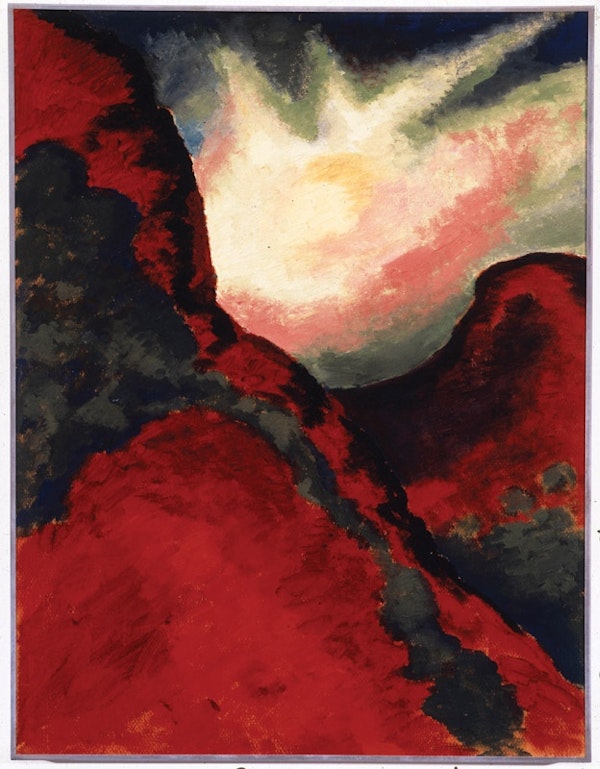

O'Keeffe, who loved sunsets and dawns, began painting the landscapes he saw on his walks. The result is a series of paintings of Palo Duro Canyon. Dramatic contrasts are created when the sun rises and sets.

The colors of the landscape, shrouded in darkness, and the shining sunlight are expressed in vivid colors in this series of outstanding works.

O'Keeffe did not make that many sketches before beginning to paint the tableaus. Rather, he was interested in improvising his work as he painted.

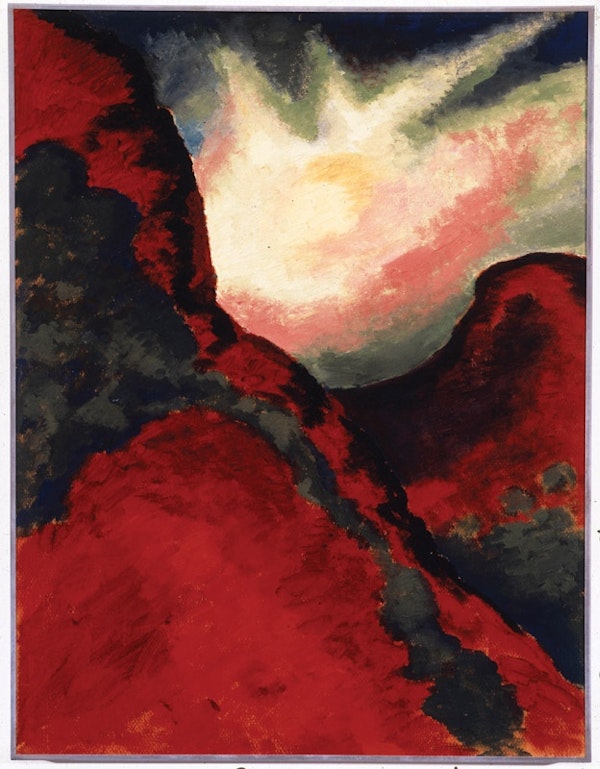

Red Landscape, 1916 -1917, Panhandle Historical Museum

The originality of her work lies in the fact that it is "both an abstraction and a landscape at the same time.

Beginning with her series of paintings in Palo Duro Canyon, O'Keeffe explored ways to express her emotional side through the simplicity of her landscapes.

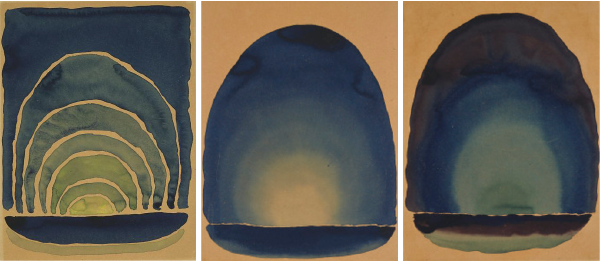

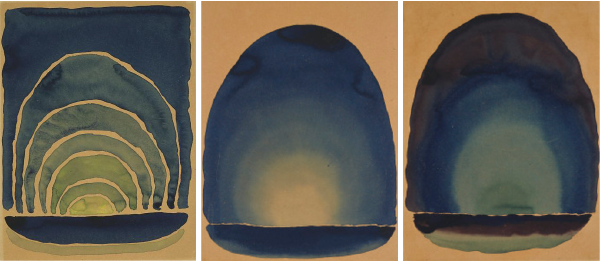

With her series of watercolors entitled "Light Rising on the Horizon," O'Keeffe was convinced that she had achieved the simplest expression of what she wanted to express.

This fusion of abstraction and figuration evolved into one of O'Keeffe's most distinctive features, but her growing relationship with Stieglitz encouraged her to stop using watercolor.

This was because the conventional wisdom in the art world at the time was that watercolors were for amateur women painters.

From then on, O'Keeffe began to make tableaux in oil paint.

Light Rising on the Horizon, 1917

In 1918, Stieglitz, who was 24 years older than O'Keeffe, offered her financial support and a place to stay in New York.

O'Keeffe gradually developed a rapport with Stieglitz, who also began to associate with various painters and photographers around him.

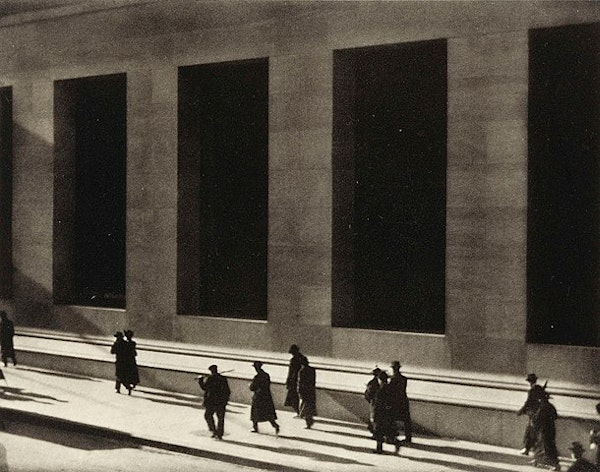

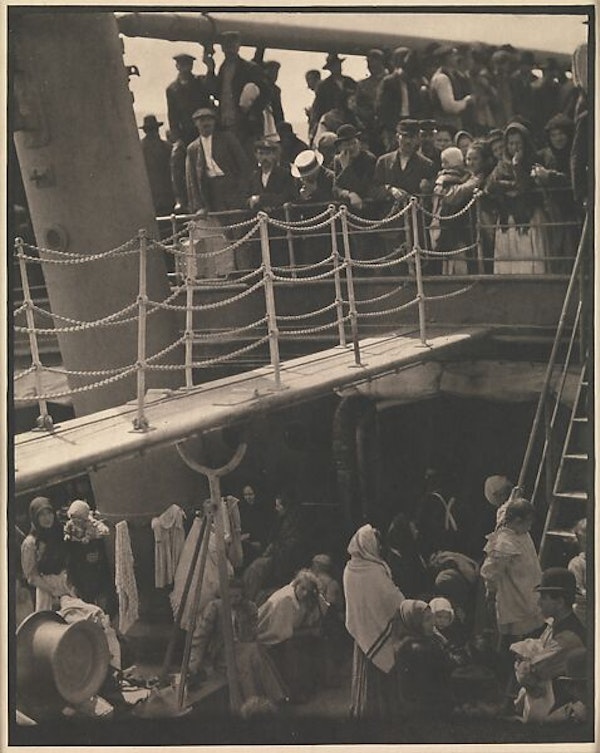

Among them was photographer Paul Strand, who, along with Stieglitz's own photographs, is considered a major influence on O'Keeffe.

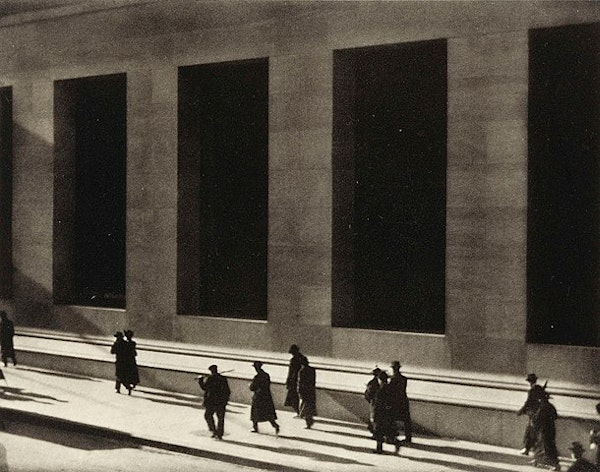

Paul Strand, Wall Street, 1915

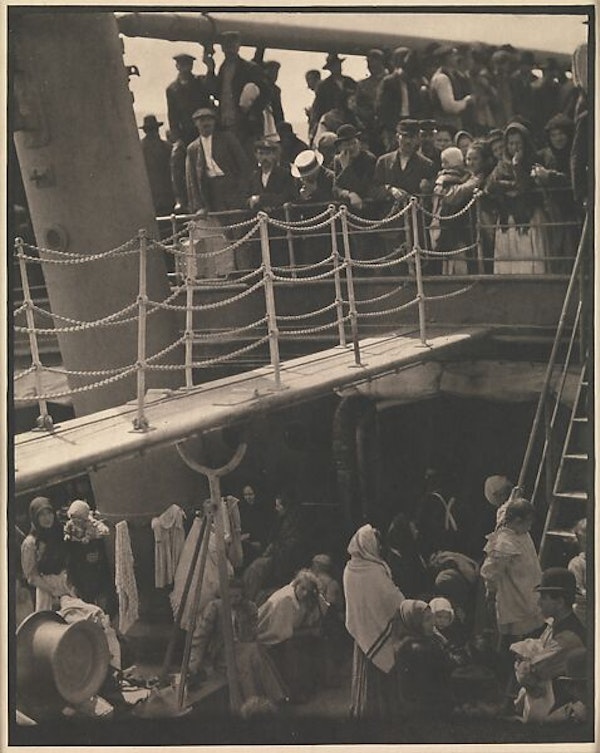

Alfred Stieglitz, "Steering," 1907, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Around this time, O'Keeffe began to produce paintings that could be considered geometric in form, using flowers, leaves, and rocks as motifs.

Green Apples," painted in 1922, is one of his most representative works.

Around the time he painted this work, O'Keeffe said, "It is not possible to reach the true meaning of things.

"It is only by selection, by elimination, and by emphasis that we arrive at the true meaning of things."

Another representative work is "Blue and Green Music," in which he reduced natural motifs to geometric elements.

Music in Blue and Green, 1921.

O'Keeffe painted approximately 200 "flower paintings" during her lifetime, making them her masterpieces.

In them, the interiors of originally small flowers are painted on a scale so large that they overhang the huge canvas, as if seen through a magnifying lens.

The "Onigeshi" and "Red Canna" series are the best examples of this characteristic.

The blood-red color of these works instantly impresses the viewer, giving the flowers a sense of life and even a kind of fear of life that is more than just beautiful.

Onigeshi, 1928

Red Canna, 1927

In 1922, Paul Rosenfeld commented that "O'Keeffe's work is pervaded by femininity.

The colors and forms in her paintings, especially those of flowers, are said to evoke the female genitalia.

Although the view that O'Keeffe's paintings are metaphors for femininity is becoming formulated, O'Keeffe herself consistently rejected such a connotation.

But even setting aside the debate over the meaning of the work, the value of O'Keeffe's work continues to soar.

In November 2014, "Jimson Weed No. 1" sold for $44 million (about $4.66 billion at the time).

This price was more than three times the price of previous works by female artists, which shows O'Keeffe's high reputation.

Jimson Weed, 1936

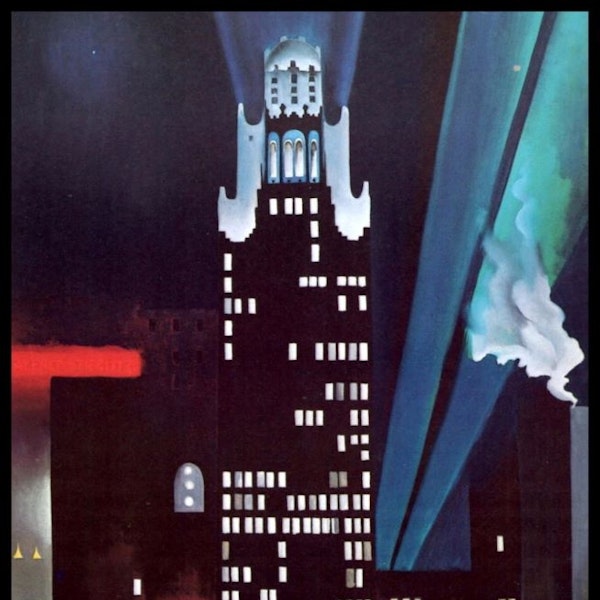

In 1925, O'Keeffe moved into a 30th-floor apartment at the Shelton Hotel in Manhattan, New York, and began painting skyscrapers and skyscrapers as motifs.

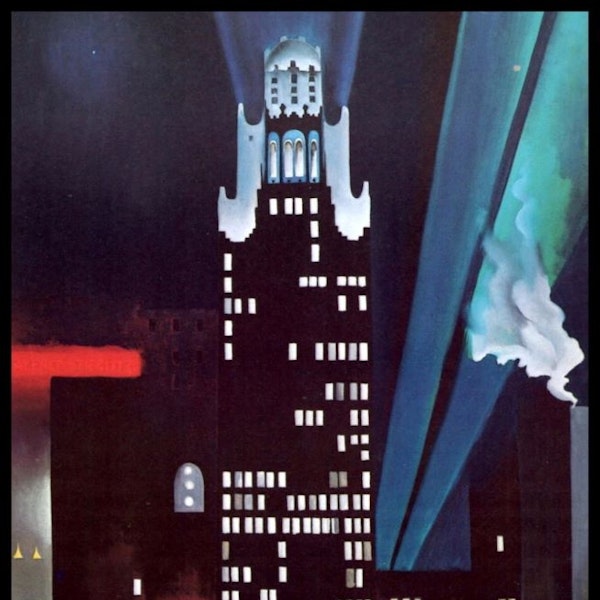

Radiator Building" is perhaps the work that most reveals O'Keeffe's painting technique and the geometry of simplification.

The Shelton Hotel is lit up, and the highway running through the gap between the buildings is illuminated, creating a fantastic atmosphere.

While O'Keeffe's unique use of vivid colors is evident in this work, the restrained use of color to suit the night scene makes it a very popular work.

The Radiator Building, 1927

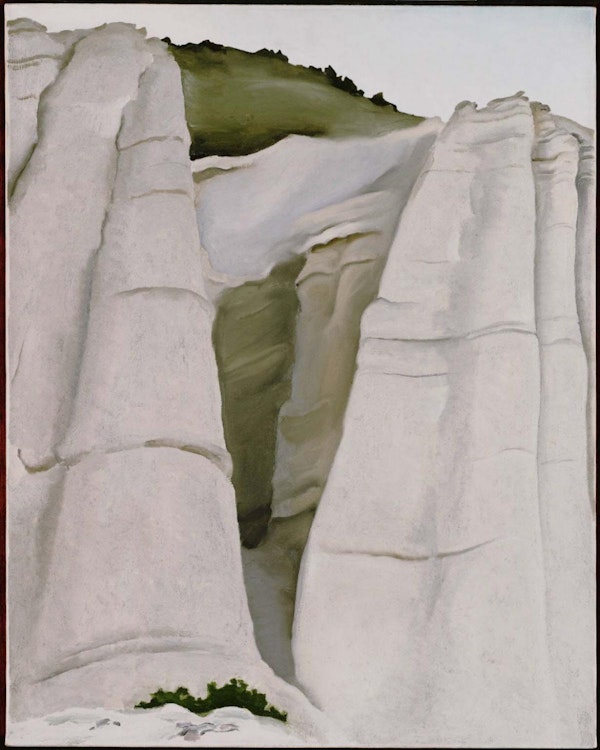

In 1929, O'Keeffe and his friend Rebecca Strand visited Taos, New Mexico, where they were greatly inspired.

In Taos, they stayed with Mabel Luhan, who at the time was actively supporting women artists.

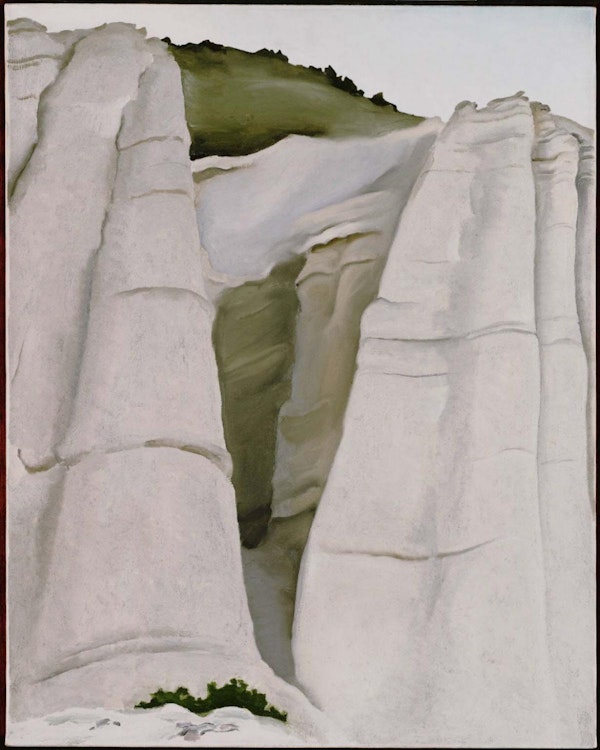

O'Keeffe continued sketching and researching in the landscape of Taos, which could be seen from the house where she was staying, and which evoked the simplicity of nature, with its rugged, rough rock surfaces.

O'Keeffe began to spend some of each year in New Mexico, collecting bones and stones that he found along the roadside during his walks and interviews.

These motifs led to a series of paintings of bones, which focused on the theme of the death of life.

His walks in the wilderness were driven in his favorite Ford A.

O'Keefe had a particular fondness for the land of New Mexico, telling a friend.

It's a really beautiful, unexplored, somewhat lonely place. It's a very 'far away place,' a place that I've painted before and still feel like I have to paint there again.

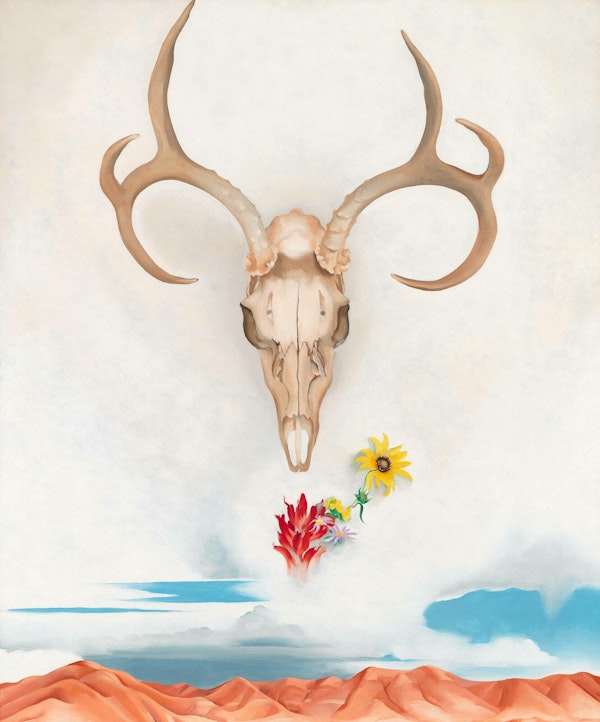

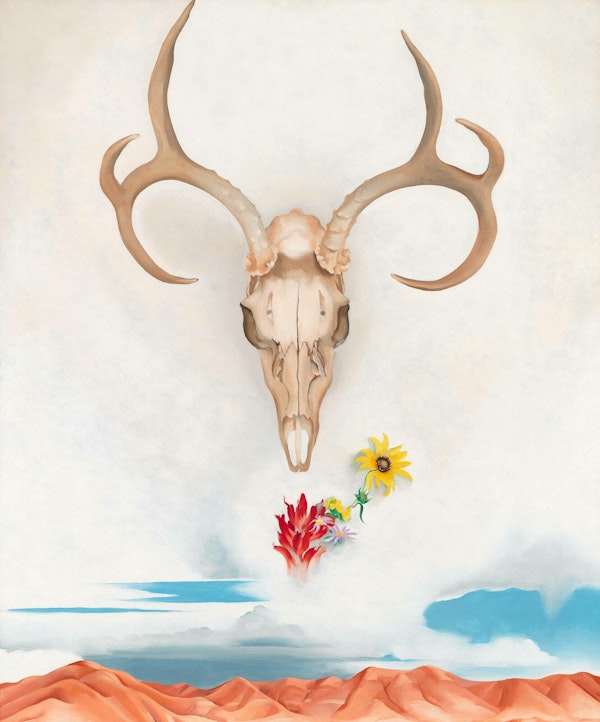

Paintings featuring cow skulls were made around this time and after the late 1930s.

From 1932 to the late 1930s, her work was interrupted by psychological problems. It is said that this was due to an affair with her husband Alfred.

In 1936, however, O'Keeffe resumed work, including perhaps one of her best-known paintings, "Summer Days.

In this work, a cow skull floats in the air, as if in surrealism, overlooking a mountain range and horizon made of red New Mexican soil.

While retaining a nostalgic and endearing quality, the composition of the painting clearly evokes a more full-fledged sense of death and mourning than was present in the flower paintings of the time.

Summer Day, 1936

When N. W. Ayer & Son, one of the oldest advertising agencies in the United States, asked O'Keeffe to collaborate with them, he readily accepted.

Artists who had worked with N. W. Ayer & Son in the past included Isamu Noguchi.

The project took O'Keeffe to Hawaii, where he spent nine weeks on the islands of Oahu, Maui, Kauai, and the main Hawaiian Islands.

In Maui, in particular, O'Keefe was given a completely free time to concentrate on his research for the production of the film.

Based on this research, O'Keeffe returned to New York and completed 20 paintings of voluptuous, back-and-forth plants.

Pineapple Buds, 1939.

In the 1940s, retrospectives were held at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.

A solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1946 made her the first female artist to have a solo exhibition at the museum.

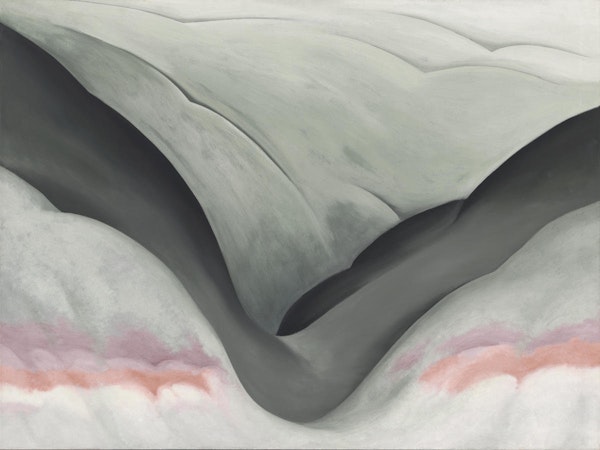

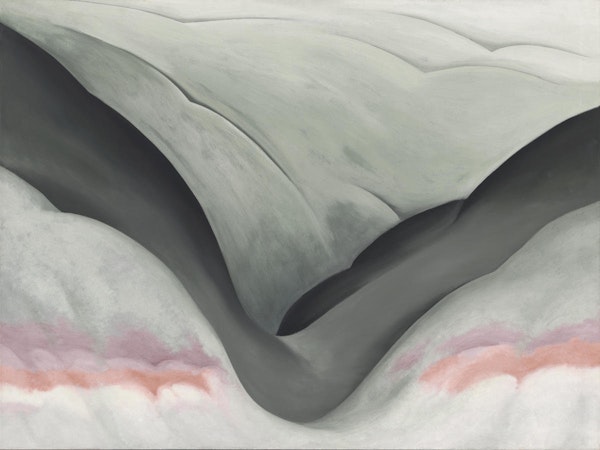

Around the time of the retrospective, O'Keeffe began the series Black Land and White Land.

The Black Land, according to O'Keeffe, was "like miles of elephant backs and soles covered in white sand.

In Abiquiú, New Mexico, the land was marked by white, sheer cliffs.

The paintings from this period, which could be called a series of achromatic black, gray, and white, are more abstract.

Black Land II, 1942, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Black Land, Gray and Pink, 1949

The White Land, 1941

In his later years, O'Keeffe painted symbolic paintings featuring ladders leading to the heavens and mysterious, floating paintings that seem to look down from above the clouds.

In these paintings, he departed from his previous abstract style of painting, which remained faithful to observation, and adopted a compositional style that left nothing to the imagination.

Even in his late years, O'Keeffe continued to search for new ways to create art, and his insatiable appetite is evident.

Ladder to the Moon, 1958

Landscape Above the Clouds IV, 1965

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Worcester Art Museum and the Whitney Museum of American Art also held retrospectives of O'Keeffe's work.

The Whitney Museum of American Art also published a catalog featuring her work.

In the 1970s, until her final years in 1984, O'Keeffe continued to work in pencil, charcoal, and watercolor.

In her "The Dinner Party" (1979), artist Judy Chicago, who promoted the feminist movement, reviewed the history of women artists and singled out O'Keeffe as "the first to bring sensual, feminist iconography into the history of art. O'Keeffe herself, however, was not a feminist.

O'Keeffe herself, however, avoided being called a feminist, an artist who promoted that notion, or a "woman artist.

She preferred to be called simply "the artist.

It was pointed out from the outset that O'Keeffe's series of floral paintings symbolized the vulva of the female genitalia.

Art dealer Samuel Coutts took issue with the sexual representation in her work.

However, O'Keeffe's own position was that there was no connection between the paintings and this.

O'Keeffe insisted, "Anyone who reads erotic themes into my paintings is rather reading their own desires into them.

Muriel Napoli

Nature 133 by Muriel Napoli

Mukhamadeyeva Zulfiya

Admiration by Mukhamadeyeva Z ulfiya

Jooha Sim

Poppies keep blooming by Jooha Sim

View the latest TRiCERA ART artwork

TRiCERA ART members enjoy a variety of benefits and preferences.

- Discounts, including members-only secret sales and coupons

- Create your own collection by registering your favorite artists

- Receive updates on popular artists, exhibitions, and events

- Receive a weekly newsletter with selected art

- Personal Assessment to find out what kind of art you like.

Please register as a member for free and receive the latest information.

Writer

TRiCERA ART

Best known for her floral paintings, New York City cityscapes, and New Mexico mountain landscapes, Georgia O'Keefe was an active 20th century American artist.

In the early 20th century, O'Keefe was at the forefront of American Modernism as a female artist, a rarity at the time, and was regarded as a leading figure in the movement.

She is known for her paintings of flowers, in which colorful blossoms are enlarged to create the appearance of abstraction, as well as her landscapes of New Mexico, which she worked on in her later years.

In this issue, we will take a look at O'Keeffe's life and the major influence she had on contemporary art.

Red Canna, 1924.

Born: November 15, 1887 - March 6, 1986 (died at age 98)

Birthplace: Wisconsin, U.S.A.

Art Movement: American Modernism, Precisionism

Education: Art Institute of Chicago, Art Students League of New York, Columbia University

Associated People: Alfred Stieglitz, husband, leading American photographer and art dealer

Georgia O'Keeffe was born in 1887 in a farming family in Sun Prairie, a town not far from Lake Michigan, one of the Great Lakes of the United States.

The O'Keefe family had seven siblings, and Georgia was the second child from the top.

O'Keeffe was known for his extremely precocious artistic talent and decided to become a painter at the tender age of 10. Along with his sisters Ida and Anita, he began studying with a local watercolorist named Sarah Mann.

In 1905, at the age of eight, he enrolled at the Art Institute of Chicago. There, he was consistently rated at the top of his class.

He took a leave of absence from school in 1906-7 due to typhoid fever, and in 1907 he entered the Art Students League in Manhattan, New York.

In 1908, he won the Art Students League's Still Life Award for his painting "Dead Rabbit with Copper Pot.

As a bonus for winning this prize, she traveled to New York City, where she toured the art gallery 291, which was co-owned by her future husband, Alfred Stieglitz.

Dead Rabbit and Copper Pot, 1908

After his parents' business and health misfortunes left him without funds to continue his studies at the Academy of Fine Arts, O'Keeffe quit school in 1908 and began working as a professional illustrator.

He worked until 1910, and then moved with his family to Charlottesville, Virginia, that same year, despite a bout of measles and other illnesses.

At this time, he stopped oil painting for about four years, and it is said that he later said that the smell of turpentine oil made him sick.

It was here that O'Keeffe attended a summer school for art courses at the University of Virginia, where he was exposed to the style of a painter named Arthur Wesley Dow, and was struck by its freshness.

His style was highly design-oriented, influenced by the Japanese art that dominated the Parisian art world at the time, and O'Keeffe began experimenting with more flat compositions, replacing the traditional realism of his earlier work.

From 1912-14, he taught art classes and worked as a teacher in Amarillo, Texas.

Untitled (Rotunda at the University of Virginia), 1912 - 1914

In 1915, O'Keeffe taught an art course at Columbia University.

The charcoal drawings she was working on at this time gave form to her own inner feelings and began to show her creative expression.

The drawings were sent to a friend of O'Keeffe's and eventually caught the eye of Stieglitz at 291 Gallery.

He praised O'Keeffe's work as "the purest, most beautiful, and most sincere thing I have seen at 291 for some time now," and in April 1916, ten of O'Keeffe's drawings were exhibited at the 291 Gallery.

Drawing 13, 1915

After completing his work in Columbia, Keefe moved to Texas.

O'Keeffe, who loved sunsets and dawns, began painting the landscapes he saw on his walks. The result is a series of paintings of Palo Duro Canyon. Dramatic contrasts are created when the sun rises and sets.

The colors of the landscape, shrouded in darkness, and the shining sunlight are expressed in vivid colors in this series of outstanding works.

O'Keeffe did not make that many sketches before beginning to paint the tableaus. Rather, he was interested in improvising his work as he painted.

Red Landscape, 1916 -1917, Panhandle Historical Museum

The originality of her work lies in the fact that it is "both an abstraction and a landscape at the same time.

Beginning with her series of paintings in Palo Duro Canyon, O'Keeffe explored ways to express her emotional side through the simplicity of her landscapes.

With her series of watercolors entitled "Light Rising on the Horizon," O'Keeffe was convinced that she had achieved the simplest expression of what she wanted to express.

This fusion of abstraction and figuration evolved into one of O'Keeffe's most distinctive features, but her growing relationship with Stieglitz encouraged her to stop using watercolor.

This was because the conventional wisdom in the art world at the time was that watercolors were for amateur women painters.

From then on, O'Keeffe began to make tableaux in oil paint.

Light Rising on the Horizon, 1917

In 1918, Stieglitz, who was 24 years older than O'Keeffe, offered her financial support and a place to stay in New York.

O'Keeffe gradually developed a rapport with Stieglitz, who also began to associate with various painters and photographers around him.

Among them was photographer Paul Strand, who, along with Stieglitz's own photographs, is considered a major influence on O'Keeffe.

Paul Strand, Wall Street, 1915

Alfred Stieglitz, "Steering," 1907, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Around this time, O'Keeffe began to produce paintings that could be considered geometric in form, using flowers, leaves, and rocks as motifs.

Green Apples," painted in 1922, is one of his most representative works.

Around the time he painted this work, O'Keeffe said, "It is not possible to reach the true meaning of things.

"It is only by selection, by elimination, and by emphasis that we arrive at the true meaning of things."

Another representative work is "Blue and Green Music," in which he reduced natural motifs to geometric elements.

Music in Blue and Green, 1921.

O'Keeffe painted approximately 200 "flower paintings" during her lifetime, making them her masterpieces.

In them, the interiors of originally small flowers are painted on a scale so large that they overhang the huge canvas, as if seen through a magnifying lens.

The "Onigeshi" and "Red Canna" series are the best examples of this characteristic.

The blood-red color of these works instantly impresses the viewer, giving the flowers a sense of life and even a kind of fear of life that is more than just beautiful.

Onigeshi, 1928

Red Canna, 1927

In 1922, Paul Rosenfeld commented that "O'Keeffe's work is pervaded by femininity.

The colors and forms in her paintings, especially those of flowers, are said to evoke the female genitalia.

Although the view that O'Keeffe's paintings are metaphors for femininity is becoming formulated, O'Keeffe herself consistently rejected such a connotation.

But even setting aside the debate over the meaning of the work, the value of O'Keeffe's work continues to soar.

In November 2014, "Jimson Weed No. 1" sold for $44 million (about $4.66 billion at the time).

This price was more than three times the price of previous works by female artists, which shows O'Keeffe's high reputation.

Jimson Weed, 1936

In 1925, O'Keeffe moved into a 30th-floor apartment at the Shelton Hotel in Manhattan, New York, and began painting skyscrapers and skyscrapers as motifs.

Radiator Building" is perhaps the work that most reveals O'Keeffe's painting technique and the geometry of simplification.

The Shelton Hotel is lit up, and the highway running through the gap between the buildings is illuminated, creating a fantastic atmosphere.

While O'Keeffe's unique use of vivid colors is evident in this work, the restrained use of color to suit the night scene makes it a very popular work.

The Radiator Building, 1927

In 1929, O'Keeffe and his friend Rebecca Strand visited Taos, New Mexico, where they were greatly inspired.

In Taos, they stayed with Mabel Luhan, who at the time was actively supporting women artists.

O'Keeffe continued sketching and researching in the landscape of Taos, which could be seen from the house where she was staying, and which evoked the simplicity of nature, with its rugged, rough rock surfaces.

O'Keeffe began to spend some of each year in New Mexico, collecting bones and stones that he found along the roadside during his walks and interviews.

These motifs led to a series of paintings of bones, which focused on the theme of the death of life.

His walks in the wilderness were driven in his favorite Ford A.

O'Keefe had a particular fondness for the land of New Mexico, telling a friend.

It's a really beautiful, unexplored, somewhat lonely place. It's a very 'far away place,' a place that I've painted before and still feel like I have to paint there again.

Paintings featuring cow skulls were made around this time and after the late 1930s.

From 1932 to the late 1930s, her work was interrupted by psychological problems. It is said that this was due to an affair with her husband Alfred.

In 1936, however, O'Keeffe resumed work, including perhaps one of her best-known paintings, "Summer Days.

In this work, a cow skull floats in the air, as if in surrealism, overlooking a mountain range and horizon made of red New Mexican soil.

While retaining a nostalgic and endearing quality, the composition of the painting clearly evokes a more full-fledged sense of death and mourning than was present in the flower paintings of the time.

Summer Day, 1936

When N. W. Ayer & Son, one of the oldest advertising agencies in the United States, asked O'Keeffe to collaborate with them, he readily accepted.

Artists who had worked with N. W. Ayer & Son in the past included Isamu Noguchi.

The project took O'Keeffe to Hawaii, where he spent nine weeks on the islands of Oahu, Maui, Kauai, and the main Hawaiian Islands.

In Maui, in particular, O'Keefe was given a completely free time to concentrate on his research for the production of the film.

Based on this research, O'Keeffe returned to New York and completed 20 paintings of voluptuous, back-and-forth plants.

Pineapple Buds, 1939.

In the 1940s, retrospectives were held at the Art Institute of Chicago and the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) in New York.

A solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1946 made her the first female artist to have a solo exhibition at the museum.

Around the time of the retrospective, O'Keeffe began the series Black Land and White Land.

The Black Land, according to O'Keeffe, was "like miles of elephant backs and soles covered in white sand.

In Abiquiú, New Mexico, the land was marked by white, sheer cliffs.

The paintings from this period, which could be called a series of achromatic black, gray, and white, are more abstract.

Black Land II, 1942, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Black Land, Gray and Pink, 1949

The White Land, 1941

In his later years, O'Keeffe painted symbolic paintings featuring ladders leading to the heavens and mysterious, floating paintings that seem to look down from above the clouds.

In these paintings, he departed from his previous abstract style of painting, which remained faithful to observation, and adopted a compositional style that left nothing to the imagination.

Even in his late years, O'Keeffe continued to search for new ways to create art, and his insatiable appetite is evident.

Ladder to the Moon, 1958

Landscape Above the Clouds IV, 1965

During the 1960s and 1970s, the Worcester Art Museum and the Whitney Museum of American Art also held retrospectives of O'Keeffe's work.

The Whitney Museum of American Art also published a catalog featuring her work.

In the 1970s, until her final years in 1984, O'Keeffe continued to work in pencil, charcoal, and watercolor.

In her "The Dinner Party" (1979), artist Judy Chicago, who promoted the feminist movement, reviewed the history of women artists and singled out O'Keeffe as "the first to bring sensual, feminist iconography into the history of art. O'Keeffe herself, however, was not a feminist.

O'Keeffe herself, however, avoided being called a feminist, an artist who promoted that notion, or a "woman artist.

She preferred to be called simply "the artist.

It was pointed out from the outset that O'Keeffe's series of floral paintings symbolized the vulva of the female genitalia.

Art dealer Samuel Coutts took issue with the sexual representation in her work.

However, O'Keeffe's own position was that there was no connection between the paintings and this.

O'Keeffe insisted, "Anyone who reads erotic themes into my paintings is rather reading their own desires into them.

Muriel Napoli

Nature 133 by Muriel Napoli

Mukhamadeyeva Zulfiya

Admiration by Mukhamadeyeva Z ulfiya

Jooha Sim

Poppies keep blooming by Jooha Sim

View the latest TRiCERA ART artwork

TRiCERA ART members enjoy a variety of benefits and preferences.

- Discounts, including members-only secret sales and coupons

- Create your own collection by registering your favorite artists

- Receive updates on popular artists, exhibitions, and events

- Receive a weekly newsletter with selected art

- Personal Assessment to find out what kind of art you like.

Please register as a member for free and receive the latest information.

Writer

TRiCERA ART